![]() |

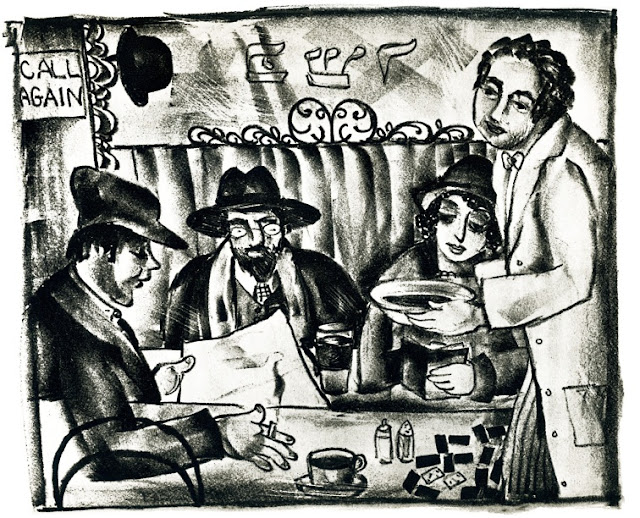

| Bateman the Opticians, Croydon, from 'The Unsophisticated Arts' |

Since I first came across Barbara Jones' extraordinary book 'The Unsophisticated Arts' a few years ago I've been wondering when somebody would reissue it, and now independent publisher

Little Toller Books has gone a step further. As with their previous titles they haven't simply reprinted the original edition but have substantially redesigned it, decluttering a spread here and updating an illustration there. The new edition is lighter, brighter and more colourful than the original, which was printed on paper made out of recycled porridge (it was 1951, after all). A little of the chiaroscuro of Jones's vision is lost - the photos of roundabout horses are not quite as black and sinister as they were previously - but all in all this is a fantastic book. Buy it now!

![]() |

| Barbara Jones enjoying her work - what is that peculiar ornament on the bookshelf? |

I meant to write a post on Joan Eardley last week, after reading Christopher Andreae's

wonderful new book, but time got away from me. Neither Eardley nor Jones lived as long as they should have, and both had a fascination for the local and particular that went down badly with critics of the time but which now makes them - to my mind - seem doubly valuable as fine artists and chroniclers of everyday life. While Eardley became well-known for her paintings of children from now-vanished Glasgow slums, Jones is now recognised as one of the most significant arbiters of modern taste.

![]() |

| No detail too small... Interior of a canal boat, from 'The Unsophisticated Arts' |

In a Foreword to the new edition, Peter Blake notes that 'I have no doubt that discovering Barbara Jones was one of the more important things that happened to me, and helped form the way I work.' In her books and in her almost unclassifiable 1951 exhibition 'Black Eyes and Lemonade', Jones introduced what she called 'the vernaculars' to a culture desperate for some alternative to pretentious, soulless modernism. She wasn't worried about distinctions between folk and machine-made art but stuck them altogether, choosing work that was, as she put it 'bold and fizzy.'

![]() |

| Never judge a book by its cover? Maybe in this case... |

Her books show a similarly eclectic spirit. 'The Unsophisticated Arts' combines chapters on tattooing and the seaside, amusement arcades and taxidermy, each illustrated with a mixture of photographs, line drawings and paintings. It is disorderly, intensely personal and obsessive, but at the same time the book hangs together perfectly.

![]() |

| Ravilious would have loved this, from 'The Unsophisticated Arts' |

It helps that Jones was also an excellent writer, the kind who (I imagine) wrote down words as she would have spoken them. Like her contemporary Olive Cook she writes seriously about her subject in a way that an intelligent child could understand perfectly - and enjoy too. I love this introduction to the chapter on Roundabouts:

When the Romans left England there were a thousand dull years filled only with ballads, pipe and tabor, folk dancing and maypoles. Gradually, however, the fairs emerge from the manuscripts, the tumblers and dancing bears begin to perform, and at last there is something to look at.![]() |

| from 'Recording Britain', early 1940s (V&A) |

Here and there you hear echoes of earlier books like 'High Street', as in the chapter on shopkeeping, where we visit a butcher's that Ravilious would have recognised, complete with 'butcher's cat, noticeably sleek, and apparently unmoved even by the sale of liver'. It would have been fun if Jones had written the text of 'High Street', given her eye for the aesthetics of shops:

He makes beautiful patterns with carcasses and joints and festoons of sausages or, when meat is scarce, he hangs up sheets of paper by their corners, cut into patterns if he has time, and heightened with loops of black pudding.![]() |

Interior of saddler's shop, Croydon, from 'Recording Britain' (V&A)

I wonder if this was her Dad's place, as he was a successful Croydon saddler. |

Born in 1912 a decade later than Ravilious, Bawden, Peggy Angus and Enid Marx, Barbara Jones trained at the RCA in the 1930s and cut her teeth on the 'Recording Britain' project during the early part of World War Two. Among the myriad pictures of old houses, pubs and quintessentially English scenes, Jones's work stands out. She was clearly much more than a topographical painter, imbuing her subjects with personality. A light touch and a sure eye were hers from the start.

![]() |

| St Mary's Homes and Chapel, Godstone, 'Recording Britain' (V&A) |

![]() |

| Fairground litho, 1946 (V&A) - there's a detailed chapter on this subject in 'The Unsophisticated Arts' |

I suspect that many artists besides Peter Blake owe a debt to Barbara Jones; she looked about her with keen eyes, found subjects no-one had bothered with before and took her discoveries seriously - but never too seriously. One of her more extraordinary achievements was the book 'Design for Death', in which she expanded on the final chapter of 'The Unsophisticated Arts', exploring all the 'beautiful, vulgar, frightening and propitiatory things that people make when confronted by that shocking and unwelcome reminder, the death of another'. The cover alone is remarkable, both beautiful and grotesque; I hope that her own death in 1978 was commemorated in suitable style.

![]() |

| An extraordinary cover for an extraordinary book... |

![]() |

| On a lighter note... an illustration from 'The Unsophisticated Arts' |

Recently, Barbara Jones has become known to a wider public, thanks in part to the tireless Ruth Artmonsky and her 2008 tribute

'A Snapper Up of Unconsidered Trifles'. At the moment The Whitechapel Gallery are hosting an exhibition about

'Black Eyes and Lemonade', and in June there's going to be a selling show of work from Jones's own collection at

Burgh House in Hampstead. The pieces below will be featured. Meanwhile, if you want to know a bit more about her books, there's a nice page at

Ash Rare Books.

![]() |

| Original artwork for 'Gift Book', on display at Burgh House, Hampstead, June 2013 |

![]() |

| Original artwork from 'The Unsophisticated Arts' - also at Burgh House |

![]() |

| Stook Duck Houses, Calbourne Water Mill, Isle of Wight |

She was the author of three important books that significantly affected the taste and perception of her contemporaries in ways that more famous artists have never succeeded in doing. The first, The Unsophisticated Arts (1951), opened people’s eyes to the art in everyday life … and that the enjoyment of art was not restricted to an educated few, but was available for the enjoyment of all. It is difficult to over-emphasise her work in this area, but one can see the effects in the displays in almost every museum and gallery throughout the country today. The second, Follies and Grottoes, developed an entirely new field for architectural and building historians, and led to the founding of an international society … The third, Design for Death (1967), sparked a similar fashion for the study of funeral customs, cemeteries, and artifacts associated with death … How many other artists and writers can boast of having achieved so much in changing the perception and temper of succeeding generations? … The roll-call of English artists in the twentieth century is not so lengthy that we can afford to overlook such a distinctive figure. (BC Bloomfield –

The Life and Work of Barbara Jones [1912-1978] via

Ash Rare Books)

All work shown is the copyright of Barbara Jones's estate.